Platt Amendment

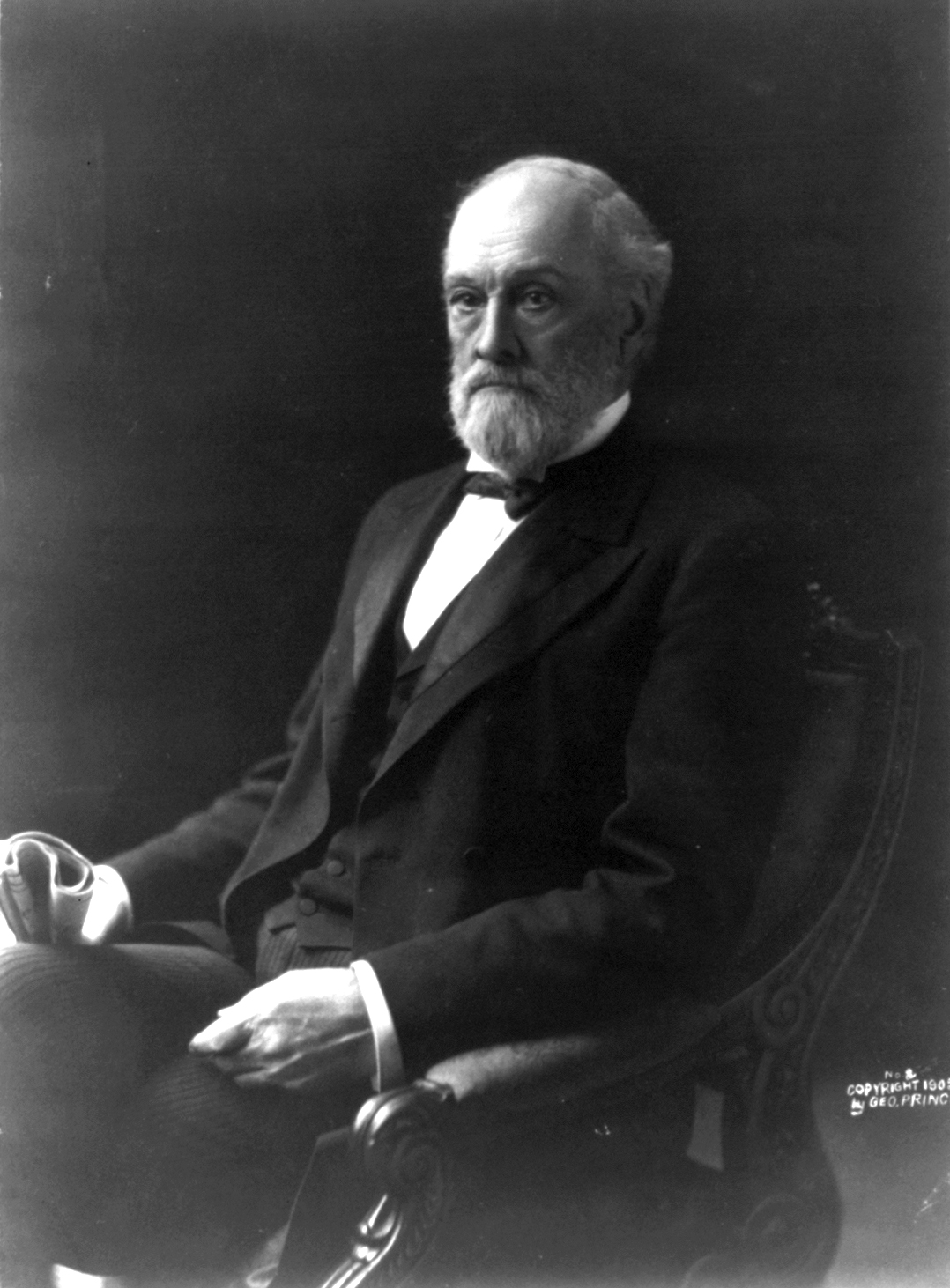

The Platt Amendment, an amendment to a U.S. army appropriations bill, established the terms under which the United States would end its military occupation of Cuba (which had begun in 1898 during the Spanish-American War) and "leave the government and control of the island of Cuba to its people." While the amendment was named after Senator Orville Platt of Connecticut, it was drafted largely by Secretary of War Elihu Root. The Platt Amendment laid down eight conditions to which the Cuban Government had to agree before the withdrawal of U.S. forces and the transfer of sovereignty would begin.

The Platt Amendment's conditions prohibited the Cuban Government from entering into any international treaty that would compromise Cuban independence or allow foreign powers to use the island for military purposes. The United States also reserved the right to intervene in Cuban affairs in order to defend Cuban independence and to maintain "a government adequate for the protection of life, property, and individual liberty." Other conditions of the Amendment demanded that the Cuban Government implement plans to improve sanitary conditions on the island, relinquish claims on the Isle of Pines (now known as the Isla de la Juventud), and agree to sell or lease territory for coaling and naval stations to the United States. (This clause ultimately led to the perpetual lease by the United States of Guantánamo Bay.) Finally, the amendment required the Cuban Government to conclude a treaty with the United States that would make the Platt amendment legally binding, and the United States pressured the Cubans to incorporate the terms of the Platt Amendment in the Cuban constitution.

The rationale behind the Platt Amendment was straightforward. The United States Government had intervened in Cuba in order to safeguard its significant commercial interests on the island in the wake of Spain's inability to preserve law and order. As U.S. military occupation of the island was to end, the United States needed some method of maintaining a permanent presence and order. However, anti-annexationists in Congress had incorporated the Teller Amendment in the 1898 war resolution authorizing President William McKinley to take action against Spain in the Spanish-American War. This Teller Amendment committed the U.S. Government to granting Cuba its independence following the removal of Spanish forces. By directly incorporating the requirements of the Platt Amendment into the Cuban constitution, the McKinley Administration was able to shape Cuban affairs without violating the Teller Amendment.

General Leonard Wood, commander of the U.S. occupation forces and military governor of Cuba, presented the terms of the Platt Amendment to the delegates of the Cuban Constitutional Convention in late 1900. Although the Cuban delegates realized that the amendment significantly limited Cuban sovereignty, and originally refused to include it within their constitution, the U.S. Government promised them a trade treaty that would guarantee Cuban sugar exports access to the U.S. market. After several failed attempts by the Cubans to reject or modify the terms of the Platt amendment, the Cuban Constitutional Convention finally succumbed to American pressure and ratified it on June 12, 1901, by a vote of 16 to 11. The Platt Amendment remained in force until 1934 when both sides agreed to cancel the treaties that enforced it.

— U.S. Department of State Archive

The Platt Amendment took its name from Senator Orville Platt, pictured here.

Map of Cuba in 1904.

This timespace is inspired by the 7th chapter of the book How to Hide an Empire, by Daniel Immerwahr. It tells the life of Puerto Rican nationalist Pedro Albizu Campos in the context of other nationalist movements and U.S. interventions in Latin America.